The 100-Year Effect

Alumnus Kent Thornburg has made it his mission to change the way we view nutrition and chronic disease – for this generation and those to come

By Jeremy Lloyd

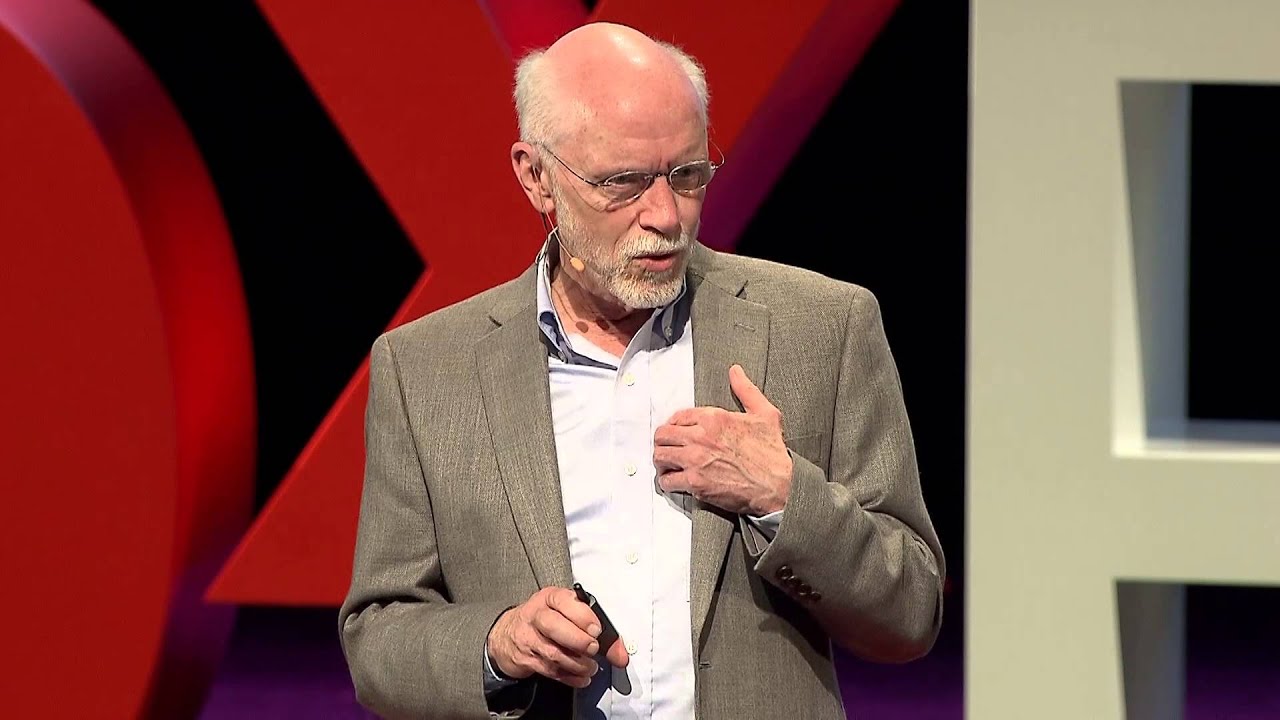

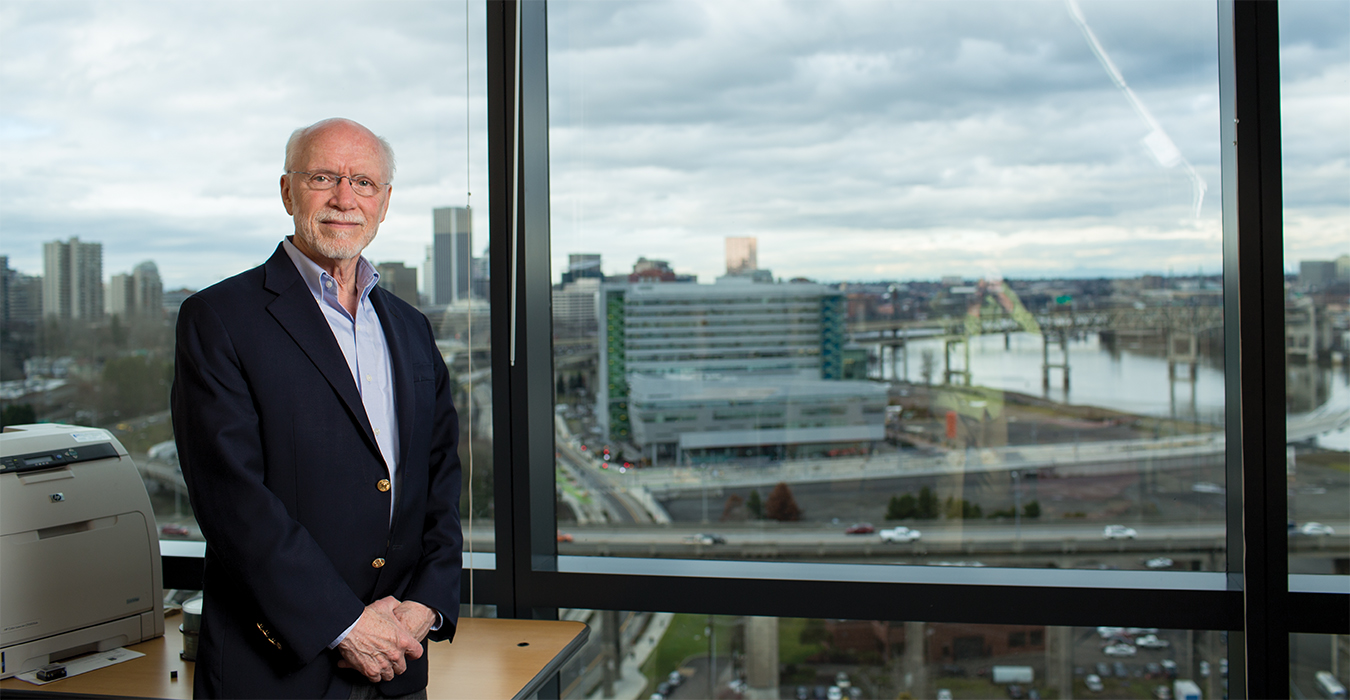

Kent Thornburg’s office is relatively unimpressive – at least for a man of his stature. It’s small, with mostly blank walls, a simple desk and a plain round table for meetings.

It’s not until you peer out the expansive floor-to-ceiling window and take in the stunning view of Portland’s South Waterfront that you remember where you are: OHSU Knight Cardiovascular Institute, 14th floor, Center for Developmental Health. Here, under Thornburg’s direction, cutting-edge research is conducted, exploring ways to prevent conditions like heart disease, type 2 diabetes and obesity. The center takes up a lion’s share of the 14th floor, teeming with scientists and laboratory assistants performing groundbreaking work on machines that cost nearly as much as one of the high-rise waterfront apartments visible in the distance.

Also visible through his office window, just past the Ross Island Bridge, is the OHSU Moore Institute. Thornburg serves as director there as well. Committed to research, clinical care and the promotion of a healthy diet, the institute was launched by a $25 million pledge from the founders of well-known natural food brand Bob’s Red Mill.

As if that weren’t enough to keep a scientist busy, Thornburg holds the titles of M. Lowell Edwards Chair and professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University, and has a myriad of honors, designations and board member positions to his name. But there are no certificates of achievement on his office walls, no pictures of him shaking hands with important people. None of that gets him excited – not in the least. What gets Thornburg out of bed in the morning is chronic disease. Or, to be more specific, ending it.

“Heart disease, diabetes, obesity, osteoporosis – for years, people have believed they are a natural part of aging,” Thornburg says. “But it turns out that chronic diseases arise because people didn’t grow well before they were born. That causes two problems: one, the structure of their newborn body might be inadequate and make them vulnerable to acquiring later disease; but the other piece of it is that their genes might be affected through this mechanism called epigenetics.”

Epigenetics, which refers to changes to the “machinery” of an organism that regulates the way in which genes are turned off and on, is key to Thornburg’s work.

“It’s possible that the nutrients you get from your mother go across the placenta, affect the baby, and those nutrients can change the expression patterns of genes in the baby,” he explains. “So now the genes can either become protected from disease, or they can actually make you more vulnerable – depending on how many nutrients and which nutrients you get. What’s profound about this is we now know that chronic disease comes from a developmental process, not by some genetic thing that happens to you as you age.”

“... we now know that chronic disease comes from a developmental process, not by some genetic thing that happens to you as you age.”

Thornburg’s voice rises with enthusiasm as he explains, as if for the first time, a field of study he’s been immersed in since 1988, when an English scientist by the name of David Barker postulated at an international conference Thornburg was attending that a person’s risk for heart disease was determined by how much they weighed when they were born. The two became friends and collaborated in their research efforts for many years, eventually bringing a controversial theory to the mainstream.

“In a few years’ time after we met – maybe within a decade – we were absolutely certain that this was right, that the way you grow before you’re born determines your risk for having heart disease later in life,” Thornburg says. “So the smaller you are before you’re born, the more likely you are to have heart disease; a person’s risk goes up the lower their weight when they are born.”

But Thornburg’s research shows it’s not just malnutrition in the womb that affects future health. “The risk also goes up again for bigger babies,” he says. “That’s because most bigger babies are born to mothers who have diabetes, and high blood sugar from the mother goes across the placenta to the baby and causes it to become too big. Those babies have a lot of risk for disease, too.”

The sweet spot, according to Thornburg, is an 8- to 9-pound baby. This weight range, he says, carries the lowest risk of future chronic disease. These days, fewer and fewer babies are hitting that mark, and the culprit is no surprise.

“The American population is in their third generation now of being malnourished, because three generations ago we started eating fast foods and abandoning the food in the garden,” Thornburg explains. “Now calories are very cheap and they’re delicious. You can eat all kinds of wonderful food that you enjoy without getting any nutrients. Each generation has gotten worse, and that means each generation is more vulnerable to diabetes and obesity than the one before.”

According to Thornburg, it’s a problem that is compounded and passed on from one generation to the next, reaching back as far as four generations, with epigenetic implications passed along from a person’s mother, father, grandparents, and even great-grandparents. He calls it the 100-year effect.

But most important, says Thornburg, is changing nutrition habits today.

“If you’re a person who is planning to have a family, a healthy diet now will make a huge difference in the health of your offspring, and this follows from one generation to the next,” he says. “That’s a very profound thing. And not many people are saying it because only a small number of scientists have studied it enough so far to understand how it works.”

Even after nearly 30 years of research, Thornburg acknowledges that many questions remain in what is still an emerging field of study that generates considerable debate within the scientific community.

“There are a series of really large gaps in our knowledge about how nutrition leads to disease,” he says, “and I won’t live long enough to figure them all out. The people I’m training now at OHSU will have to tackle these questions one at a time. There’s a lot of work to be done.”

Thornburg, a 1967 graduate of George Fox and a longtime university board of trustees member, has a passion for educating this generation of young people about the benefits of proper nutrition. It’s one of the reasons he’s involved in implementing the “Nutrition Matters” initiative at George Fox, a nutrition and fitness awareness program sponsored by a grant from Bob and Charlee Moore, the same philanthropists whose donation launched the Moore Institute.

“I’m extremely proud of George Fox University for being willing to take this on,” Thornburg says. “The Moore Institute is interested in building programs for colleges and universities all over the country, and George Fox stepped up to the plate first. It’s so urgent that we change the course of the way we’re eating.”

After all, the next 100 years starts now.

Bruin Notes

- University Readies to Celebrate 125 Years

- Study Shows University Generates $140 Million for Local Economy

- News Bits

- Powers Publishes Landmark Findings on Heat Dissipation in Hummingbirds

- George Fox, Newberg Ranked Highly for Safety

- Gift Brings ‘The Saint John’s Bible’ to Campus for Second Year

- Plans Announced for New Student Activity Center

- University Honors Top Teachers, Researchers