When Compassion Meets Crisis

by Sean Patterson

George Fox addresses the dire need for psychiatric mental health nurse practitioners with the launch of a PMHNP program in 2027 – and the hiring of a director, April Phillips, committed to bringing hope to those on the fringes of society

“Be ashamed to die until you have won some victory for humanity.”

– Horace Mann

April Phillips has seen too much brokenness, despair and heartbreak to ignore Mann’s words. They are what motivate her to do what she does – serve as a lifeline to those on society’s fringes.

For three decades she has traveled the world over – from Central Asia to South America, Europe to the deserts of the American West – and while they may differ in climate, culture, language and topography, they share a commonality: They are home to people in crisis.

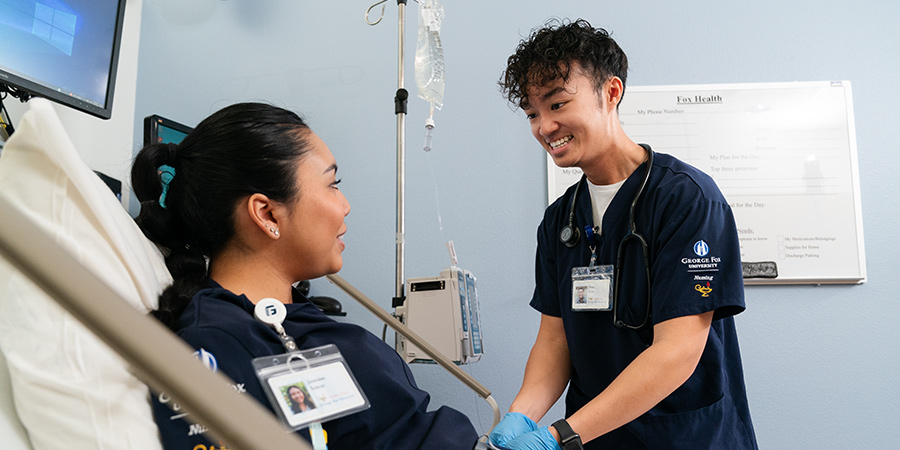

Now, as the newly hired director of the soon-to-be-launched Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner program at George Fox University – a Doctor of Nursing Practice initiative to be introduced in 2027 – Phillips is getting the opportunity to train the next generation of practitioners who will help address a dire need, particularly in rural areas.

Sobering Statistics

The numbers don’t lie: Oregon and Washington will require more than 220 new mental health practitioners to tackle the rural mental health crisis, as reported by the Health Resources and Services Administration in 2024, and Oregon is last in balancing youth mental illness and access to care, according to advocacy and monitoring nonprofit Mental Health America.

In addition, over the past 20 years, suicide rates in Oregon have increased by 34 percent, and youth and adolescent mental health outcomes are especially alarming. Oregon adolescents aged 12 to 17 report the highest rate of serious suicidal ideation in the nation, and suicide is now the second-leading cause of death for individuals ages 5 to 24.

“There is a critical need across the U.S. – we really don’t have any fully at capacity areas in our country in regard to psychiatry,” Phillips says. “And our rural areas are particularly underserved, with people waiting upwards of nine months to see a psychiatrist. We also know that 50% of all primary care visits involve some form of psychiatric complaint – some form of mental health diagnoses – so that’s huge. That’s a lot of people.”

The PMHNP program will help address this mental healthcare shortage, turning out practitioners who have the authority to prescribe psychiatric medications – a practice not permitted for those nurses without PMHNP training. In addition, PMHNPs offer therapy and counseling services while also developing comprehensive treatment plans.

Beyond that, Phillips sees the students under her care becoming beacons of hope who see each individual from a holistic perspective.

“One of the things I love about advanced practice nursing is I really feel it’s akin to the philosophy of holistic nursing,” she says. “We will be training our graduates to really treat the whole person, so that means not just medication management – it means treating the mental health issues of the individual. It means providing that valuable care and counseling, and providing for the spiritual care for the patient as well. We’re looking at the whole person.”

A Change in Plans

Phillips didn’t initially intend to work with people. Her first degree was in zoology, and she traveled the world to do research in the animal kingdom. Among her stops was the Amazon, where her eyes were opened to the high medical need among the impoverished people living in Favelas – self-built settlements that grew out of a severe housing shortage and rapid urbanization.

“It all just hit me,” she says. “Just seeing the utter poverty and lack of access to care, in Brazil and in Central Asia, was a life-changing thing. It’s hard to ignore when you see people going hungry every day. And later, seeing the dire need right here in the U.S., both in my community and in my direct family, really drove me into the field of nursing.”

Phillips went on to earn both a master of science in nursing and a doctor of nursing practice degree from Frontier Nursing University, with her doctoral research focused on the development and implementation of integrated care models that embed mental health services into primary care – an area in which she continues to be recognized as a national and international speaker.

She ultimately served as a medical director for several community-based health centers, leading initiatives to expand integrated care delivery. And, as a National Health Service Corps member and ambassador for a decade, Phillips collaborated with state and national leaders – including members of Congress, the New Mexico legislature, and former Governor Susana Martinez – to strengthen the behavioral health workforce and expand access in rural and underserved areas.

She also represented primary care providers on the New Mexico Behavioral Health Coalition, working closely with health policy leaders to address systemic gaps in care.

A Personal Connection

Phillips’ desire to make a difference as a PMHNP was further driven by the fact she had family members in need of care – and didn’t receive it. Two of her cousins, who like many Native Americans living off of the reservation with limited access to healthcare services, died of treatable conditions at a young age.

“You wouldn’t think that would happen in our modern society,” she reflects on their deaths. “But it did, and I believe it was related to a lack of access to care. To see my aunt lose two of her sons – that was hard to watch.”

In response, Phillips began serving in the National Health Service Corps, initially working in the maximum security prison system in New Mexico. “Had many of those inmates received the mental healthcare they needed, they probably wouldn’t have been there – and that was profound to me, really profound,” she says.

She also worked with several tribal communities, including the Pueblos, and served as the medical director of a rural clinic in New Mexico, complete with a hitching post for patients to hook up their horses outside when showing up for an appointment.

“I had people driving a hundred miles to see me for primary care,” she says, “so to ask those individuals to drive another four hours to Albuquerque for psychiatric care was out of the question. That’s why it was so vital for us to offer those services where we did.”

Later, she addressed the need of residents in a rural community in southwest Colorado, where she worked with the local hospital, fire department, and the Emergency Medical Services of the police department to develop a system where patients with a mental health crisis could call a hotline and be seen within 24 to 48 hours by a crisis counselor in primary care rather than visit the ER – where they may never receive the follow-up psychiatric services that they need.

“During that time, the wait to see psychiatry was anywhere from four to six months,” she adds, “so this was a huge reduction in that time span for people. We successfully diverted several people from an ER situation, and most importantly, they got the follow-up care that they really needed.”

She estimates that, from a cost-savings perspective, in one month alone medical costs were reduced more than $650,000 had patients instead visited the emergency room.

Today, Phillips runs a small private practice in Colorado, despite recently moving to Oregon. “That’s the beauty of psychiatry,” she says. “If there’s one thing that psychiatry does well, it's the utilization of technology to meet the need.”

‘Use Me How Best You Can’

Phillips herself survived a critical health event that nearly resulted in her death in 2020. And while it isn’t easy to talk about, she says it changed her perspective and her priorities.

“It really solidified my spirituality,” she says, not wishing to divulge details. “It was a wake-up call. It was like the stopping of a train. It made me stop and really ask questions like, ‘What am I doing with my life?’ and ‘How can I make a difference?’”

It was at this time Mann’s quote – one she has mounted above her desk – truly resonated.

“I really took a step back and told God, ‘Hey, use me how you best can,” she says. “Just giving into that freely, knowing that it will have a ripple effect, is a very powerful thing.”

A Serendipitous Opportunity

The ideal opportunity to generate that ripple effect – the director position of the PMHNP program at George Fox – came about by chance. A friend recommended Phillips look into it after seeing the job posted online.

“I wasn’t even looking, but I thought, ‘Why not – I’ll apply,” she recalls. “It was very serendipitous. And the more I learned about George Fox, the more inspired I was, not just with the phenomenal work that’s been done at the university level, but because every contact that I had with anyone here was really living the mission and vision. That doesn’t always happen. It can get lost in the shuffle, but you notice that, you feel that on campus.”

Her dreams for the program are ambitious – and big.

“There are several universities who are doing some great work along the West Coast. What I think will really set this program apart is at the heart of the Be Known promise. When I think about the implementation of this program, and as it grows, I see that ripple effect happening. So we’re looking at Portland as the epicenter, and I see us making a huge impact, ultimately, across the United States. My goal is to make us one of the top-five programs in the country in this discipline.”

“It's going to be more rigorous than several other programs. We will have a very rich clinical experience of a thousand hours, and we're going to have graduates who feel very comfortable working as a specialist in rural areas. Because, the reality is, when our graduates get into those areas, they will have pediatricians and all kinds of primary care providers and clinicians referring to their services. And, in many cases, they’re going to be the only qualified individuals in this field in their area.”

She is looking for students who resonate with Mann’s quote – those seeking ways to make “victories for humanity” – and sees no reason why she won’t succeed in finding them.

“We want people here who want to make a big difference,” she says. “Those who feel very driven to impact this dire need in the U.S. with compassion and empathy, with spiritual guidance and determination. My promise is we will get to know these students and support them through the hard times, because, in this profession, there are certainly hard and difficult times.”

For Phillips, the fall of 2027 can’t get here soon enough.

“It’s remarkable that the university is driven to develop the highest-quality program possible,” she says. “George Fox really wants to serve where there is a distinct need and to turn out high-quality practitioners who are going to go out there and rock the world.”