Grappling with Suffering

July 24, 2025

C.S. Lewis Devotional No. 6: Grappling with Suffering

There are so many ways that C.S. Lewis awakened my imagination that I cannot begin to cover them all in a few brief essays. The truths in Narnia aren't mere allegories of Scripture. From Lewis’s perspective, if a story is truly authentic, it will inherently reflect the singular truth found in the Bible, because Christ teaches what is true. I often find the dilemmas the children face in Narnia mirror my own in the “real” world.

There are so many ways that C.S. Lewis awakened my imagination that I cannot begin to cover them all in a few brief essays. The truths in Narnia aren't mere allegories of Scripture. From Lewis’s perspective, if a story is truly authentic, it will inherently reflect the singular truth found in the Bible, because Christ teaches what is true. I often find the dilemmas the children face in Narnia mirror my own in the “real” world.

As I have journeyed on my life path, I sometimes see the Lord and hear his voice clearly, but I choose not to follow. My choice not to follow may be the result of perceived criticism or the difficulty of completing the task itself. Inaction then seems the best course of action – let me just stay where I am.

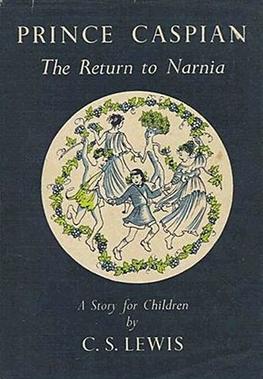

In Prince Caspian, Lucy felt the same way. The children were struggling on their journey, and she saw Aslan several times, but she chose to ignore him. She did not want to say anything to her siblings for fear that they would not believe her. So, she failed to act by engaging Aslan. When she finally changed her mind and spoke to Aslan, it was clear that it was a difficult conversation. She at first blamed her siblings for their lack of faith – “Aslan, they would not have believed me” – which always seems to be my first thought as well. Aslan did not speak; he only provided a low “growl.” Then, if that was inappropriate, Lucy changed directions and wanted to know what would have happened if she had made the “right” choice?

In Prince Caspian, Lucy felt the same way. The children were struggling on their journey, and she saw Aslan several times, but she chose to ignore him. She did not want to say anything to her siblings for fear that they would not believe her. So, she failed to act by engaging Aslan. When she finally changed her mind and spoke to Aslan, it was clear that it was a difficult conversation. She at first blamed her siblings for their lack of faith – “Aslan, they would not have believed me” – which always seems to be my first thought as well. Aslan did not speak; he only provided a low “growl.” Then, if that was inappropriate, Lucy changed directions and wanted to know what would have happened if she had made the “right” choice?

The Lion looked straight into her eyes.

The Lion looked straight into her eyes.

“Oh, Aslan,” said Lucy. “You don't mean it was? How could I—I couldn't have left the others and come up to you alone, how could I? Don't look at me like that...oh well, I suppose I could. Yes, and it wouldn't have been alone, I know, not if I was with you. But what would have been the good?”

Aslan said nothing.

“You mean,” said Lucy rather faintly, “that it would have turned out all right—somehow? But how? Please, Aslan! Am I not to know?”

“To know what would have happened, child?” said Aslan. “No. Nobody is ever told that.”

“Oh dear,” said Lucy.

“But anyone can find out what will happen,” said Aslan. “If you go back to the others now, and wake them up; and tell them you have seen me again; and that you must all get up at once and follow me – what will happen? There is only one way of finding out.”

Lewis, through his stories, depicts the children as actors in a grand play, being asked by Aslan (God) to enter into the drama with assigned tasks. They do not get to know the full story – only the part that they must play. It is their choice whether to play their role. Nevertheless, God’s redeeming grace remains for the children even amid disobedience: “Act now and we will see what happens!” The encouragement is to move into obedience, which is why Lewis did not believe in progress as it is often expressed today: “Sometimes,” he would say, “the best forward was back,” and so it was with Lucy in Prince Caspian. I find myself often in the same dilemma – playing my role but wanting to know the whole script before I act. I want to “know” before I act, but God asks me to trust and follow. It will be all right in the end – won’t it, Lord?

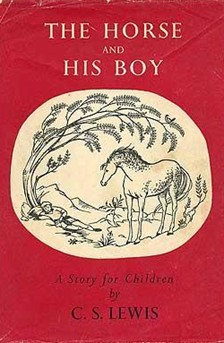

The Narnia story, The Horse and His Boy, explores one of the most difficult challenges in life: How do you understand suffering and challenge? The protagonist, the young boy Shasta, was raised under a very harsh stepfather, and told Aslan that he thought he had a bad childhood. When you read the story, you are convinced, as he is, that he is one of the most unfortunate characters in Narnia. But then he meets Aslan in the fog while riding his horse along a mountain trail.

The Narnia story, The Horse and His Boy, explores one of the most difficult challenges in life: How do you understand suffering and challenge? The protagonist, the young boy Shasta, was raised under a very harsh stepfather, and told Aslan that he thought he had a bad childhood. When you read the story, you are convinced, as he is, that he is one of the most unfortunate characters in Narnia. But then he meets Aslan in the fog while riding his horse along a mountain trail.

Aslan appears, but at the beginning of the conversation, he only hears a voice. “I do not call you unfortunate,” said the lion.

The voice then explains how he has been at the back of Shasta’s story from the beginning, guarding and guiding him so that Shasta could save Narnia and Archenland at this moment. Shasta wonders how that could be true, as he had all these negative encounters with lions. Aslan speaks: “There was only one lion ... I was the lion.”

The voice goes on to say, “I was the lion who forced you to join with Aravis. I was the cat who comforted you among the houses of the dead. I was the lion who drove the jackals from you while you slept. I was the lion who gave the horses the new strength of fear for the last mile so that you should reach King Lune in time. And I was the lion you do not remember who pushed the boat in which you lay, a child near death, so that it came to shore where a man sat, wakeful at midnight, to receive you.”

In our world of individual liberty, it is so difficult to believe that God is really sovereign and we are not in charge of our own lives. The story does not suggest that God is somehow causing the suffering or misery. There is no attempt to explain why bad things happen – they do. But he is at “the back” of our stories as well, guiding them, as we allow him, to a determined end. Each of our stories intermingle in a way we hardly imagine, but God knows what he is doing, or Aslan, as we think through this today.

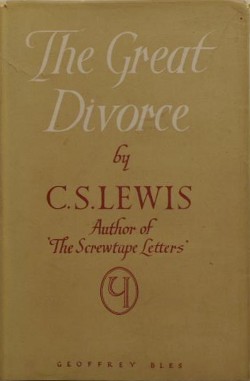

Finally, Lewis imagined heaven in ways that I had not considered. He tried to answer one of the most difficult questions in the Bible: Why would God make some people go to hell? I once thought that a good God could never send someone to the place known as the lake of fire.

In The Great Divorce, Lewis offered an alternative perspective. If heaven is the place where God’s will and desires reign in pure form, then hell is the place where individual desires are the most important. In the fictional story, people living in hell are offered a ride to heaven each morning. People climb on board, and the bus takes them to the outer reaches of heaven. There, they disembark and meet a guide who takes them on a tour. There, they discover that heaven is quite a different place – here, one loses a sense of self by submitting their will to another. In this process, the guides claim, they get back their real selves. How could that be true? Everyone on the bus has “requirements” before they agree to stay – they want to see someone, they want to know how this works, they want to know if they will be respected, and the list goes on. In the end, only one decides to stay. Heaven is a place where God’s will reigns supreme. Indeed, what if the way God sees the world is simply unacceptable to many? Why would they want to be in heaven? In the story, the explorers prefer the place where everyone gets what they want, even though it is a miserable place. In the end, Lewis notes, “all get what they want.”

In The Great Divorce, Lewis offered an alternative perspective. If heaven is the place where God’s will and desires reign in pure form, then hell is the place where individual desires are the most important. In the fictional story, people living in hell are offered a ride to heaven each morning. People climb on board, and the bus takes them to the outer reaches of heaven. There, they disembark and meet a guide who takes them on a tour. There, they discover that heaven is quite a different place – here, one loses a sense of self by submitting their will to another. In this process, the guides claim, they get back their real selves. How could that be true? Everyone on the bus has “requirements” before they agree to stay – they want to see someone, they want to know how this works, they want to know if they will be respected, and the list goes on. In the end, only one decides to stay. Heaven is a place where God’s will reigns supreme. Indeed, what if the way God sees the world is simply unacceptable to many? Why would they want to be in heaven? In the story, the explorers prefer the place where everyone gets what they want, even though it is a miserable place. In the end, Lewis notes, “all get what they want.”

Perhaps, most importantly, Lewis’s stories convey that heaven is a place of personal and corporate growth – one consistently becomes more like God in his kingdom. You are invited to go “further up and further in.” I have found that imagery so appealing. As a child, my church consistently sang hymns and provided stories that described heaven as a place where we sat on clouds and walked down streets of gold. That picture did not seem consistent with the stories I found in the biblical text. God has been about bringing his kingdom to bear in this world. The end of this earthly story seems to be the beginning of a new story. I (and those who follow God) are being invited into a new story, and the experiences here have prepared us for that work. Now that picture seems more like the God I serve!

In The Last Battle, Lewis provides a window into Aslan’s country that takes just such a theme. One might think that the story ended tragically; the children died in a railway accident. Some think it is wrong to introduce children to death so early in their lives – a sentiment Lewis did not share. But in Lewis’s world, the experience in what we call “Earth” was not the real world. Our experiences here only prepared us for what was going to happen for an eternity. We live now, for a brief time, in the shadowlands, but in the end, we are invited into the great story!

In The Last Battle, Lewis provides a window into Aslan’s country that takes just such a theme. One might think that the story ended tragically; the children died in a railway accident. Some think it is wrong to introduce children to death so early in their lives – a sentiment Lewis did not share. But in Lewis’s world, the experience in what we call “Earth” was not the real world. Our experiences here only prepared us for what was going to happen for an eternity. We live now, for a brief time, in the shadowlands, but in the end, we are invited into the great story!

Lucy said to Aslan, “We're so afraid of being sent away, Aslan. And you have sent us back into our own world so often.”

“No fear of that,” said Aslan. “Have you not guessed?”

Their hearts leaped and a wild hope rose within them.

“There was a real railway accident,” said Aslan softly. “Your father and mother and all of you are—as you used to call it in the Shadow-Lands—dead. The term is over: the holidays have begun. The dream is ended: this is the morning.”

“And as He spoke, He no longer looked to them like a lion, but the things that began to happen after that were so great and beautiful that I cannot write them. And for us this is the end of all the stories, and we can most truly say that they all lived happily ever after. But for them it was only the beginning of the real story. All their life in this world and all their adventures in Narnia had only been the cover and the title page: now at last they were beginning Chapter One of the Great Story, which no one on earth has read: which goes on for ever: in which every chapter is better than the one before.”

Humanity’s great hope is that indeed death has been defeated. We have a sense that the things we experience were not intended to be that way – we live in a fallen world. We have been promised that it will not always be this way. Christ has conquered death and redeemed this world. We are indeed experiencing the “shadowlands,” but live in light of the resurrection.

At the end of World War II, Lewis preached one of his great sermons he titled “The Weight of Glory.” In that text, he noted, “At present we are on the outside of the world, the wrong side of the door. We discern the freshness and purity of morning, but they do not make us fresh and pure. We cannot mingle with the splendours we see. But all the leaves of the New Testament are rustling with the rumour that it will not always be so. Some day, God willing, we shall get in.”

Like the Apostle Paul, we can claim that the sufferings of this present age will not compare to the glory that we shall see. Lord, may it be so.