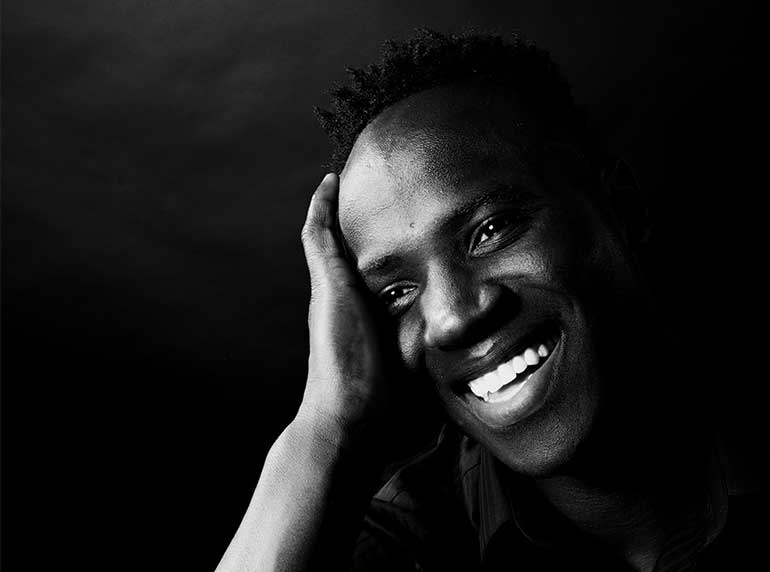

Heart of a Lion

Faced with a new culture and the memories of a harrowing past, Jonah Wafula refuses to quit

By Kimberly Felton

The nightmares aren’t what you would expect.

Not from the terror of huddling in their home through the dark night, waiting as gunfire exploded outside. Not the cries and bloody limbs the next morning as his mother carried the baby and urged him and his siblings to look straight ahead and move quickly, fleeing the Kenyan neighborhood with many others before violence resumed.

Jonah Wafula’s nightmares, rare now, spring from a time of relative peace on his uncle’s farm, several years later. A decrepit farm that he, his mother and siblings repaired – after first killing dozens of venomous snakes hiding in the cracks of the crumbling mud and dung shack built from the hard clay of Uganda. They would kill dozens more as they struck clay, forcing it to give way for a garden.

Even now, in the safety of Western Oregon where the nearest cousin to those serpents is a slender garter snake, Wafula is sure to strike first. Don’t bother telling him these snakes don’t bite.

Strong mother, strong son

Wafula is the son of a watchman, or security guard, for a hotel on the beach of Kenya’s second-largest city, Mombasa. His mother led the women in their church. He began life in this international city, with the Indian Ocean on the east and all of Kenya on the west.

Then his father caught malaria and couldn’t work. His mother fried and sold fish, trying to earn enough to feed their family of two wives and nine children. It wasn’t enough. Before long, only neighbors and their church stood between them and starvation.

Wafula was 6 the day his school sent him home early. He remembers his mother and sisters wailing. Their father had died.

Friends and neighbors urged his mom, “Why don’t you marry? Find someone to take care of the children?”

“My mother,” Wafula says, “she’s a pretty strong woman, so she said, ‘I’m not going to marry. I’m going to take care of my kids myself.’”

Wafula remembers this. And he remembers, in the difficult years that followed, his mother’s stern admonition: “Do not beg. Just work hard. Work hard for your stuff, so you appreciate it.” They would work hard, often for barely enough to live.

His mother’s determination wove into the fabric of his soul. She did not give up, and neither would he. Later, Wafula would be challenged by an entirely different world – one where he would face choices to accept gifts and opportunities he never asked for.

A night of terror

Soon after his father’s death, Wafula’s family sold everything, rented two trucks, and drove dusty back roads – more than 600 miles – to Uganda to bury his father in the land of his birth. The coffin and Wafula’s mothers and four sisters rode in the back of one truck. The five boys and their few indispensable belongings filled the back of the second. Not precisely legal, but all they could afford.

In Wafula’s world, family connections keep widows and orphans alive. An uncle took the three oldest siblings to his home in Uganda. Another uncle offered what used to be a shop in Kenya for Wafula, his mother, and the remaining three siblings. His second mother remarried, leaving her two daughters with Wafula’s mother. The family slept on the floor of the windowless brick room and cooked in their outdoor kitchen: a ring of three stones containing a fire. Wafula babysat for a neighbor, and the family collected sand along the road to sell. They made a good profit on the sand.

Then came that night. The gunshots, the screams. Wafula’s mother gathered her children in the dark, her arms outstretched to cover them. At first light they ran, with so many others, leaving everything behind. A day or two later, the entire area had been burned.

His mother remembered the way to her mother-in-law’s village – a woman Wafula had never met. They squeezed into his grandmother’s thatch-roofed hut. “She wasn’t happy about it,” he recalls. “The house was full, no food. She told my mother, ‘You have to find a way to get out of here.’”

Then his mother heard the news: Large white buses were coming. They would take the refugees to safety.

Choosing to stay together

Memories of the United Nations refugee camp in Tororo, Uganda, still make Wafula smile. “It was awesome,” he recalls. “Life changed then because police were around us, food was there, water. They gave us land to plant food. It was pretty nice.

“You know the clothes you guys donate? The U.N. brings them from the United States. They put them in a big pile. I remember the clothes we used to wear. They all smelled like really good perfume. . . . Some had money in them.”

It had been two years since his father died. Two years of struggle. Now they were safe. They played with other children. They attended school. They wore shoes and slept on mattresses with blankets. Life was good.

Then the uncle who had taken the three oldest siblings invited the rest of the family. “It was a hard decision for my mother,” Wafula says. “At the camp, we had what we needed. But with my uncle, we could be together again. My mother chose for us to be together.”

Several years passed, and the uncle’s health and wealth declined. Mother and children transitioned from guests to workers at his hotel. He fed them and paid for school. Wafula’s mother cooked while the kids pulled weeds and cleaned. Working for him was not easy. He was stern, demanding. Yet when Wafula returns to Uganda, he first will look for his uncle. “If it wasn’t for him, I don’t know where we would be,” he says. “He brought us together.”

When Wafula’s older siblings began making poor choices, his uncle sent the family to his farm – a crumbling shack with nothing more than weeds growing in the resistant land. His mother was determined and grew a garden, but food was scarce. For nine years now she had raised her children alone. Then, one day, 15-year-old Jonah told her about a mzungu – a white person – teaching tennis at a nearby orphanage. His life was about to change again.

Choosing to leave

Sarah Roome, a wife and almost-empty-nester from a farm in Oregon, had begun a tennis program for orphans through the nonprofit MAPLE (Microdevelopment Assisting the Poor through Learning and Entrepreneurship). Wafula asked if he could help.

“I liked Jonah because he was always on time,” Roome says. “He was very diligent and did everything I asked him to do. He showed more invested interest than the other kids.”

Three weeks later it was time for Roome to leave. She invited Wafula to dinner, to thank him. He shared his story. It was shocking but typical of thousands of Ugandan children. It wasn’t pity that moved Roome. She cannot say precisely what it was. “I went home that night and he got under my skin,” she says. “I began to wonder what it would take to bring him back.”

What it took was more than three months of waiting, countless bribes to officials, digging in her heels and refusing to accept “no,” and numerous interviews of both her and Wafula. “Had I known it was going to be so challenging and strenuous, I wouldn’t have done it,” Roome says. “But once I started the process, I didn’t want to back out.” An education, she believed, was the key to changing Wafula’s life.

While Roome navigated immigration’s rocky shoals, Wafula’s mother braced for another departure. Once already she had allowed her children to leave for a better opportunity. Then she gave up long-term security to bring them back together. Now, again, she would let a child go – this time not to live in another town, but on another continent, into an unfathomable new world.

‘I’m not a machine’

Wafula arrived in the U.S. at age 15 with the equivalent of a fifth-grade education – not unusual in Uganda, where many people, if they attend high school, graduate in their 20s.

His easy smile and love for people allowed him to quickly form new friendships. But he wondered why kids here had forgotten how to play. They always had a time limit, needed money, or had to go somewhere for fun. In Uganda, kids made a ball out of plastic bags and kicked it around for hours. Contentment and joy, despite empty stomachs, came easily there.

Over the next three years, Wafula started at a new high school five times, with three transfers due to visa issues. The hours Roome spent filling out and tracking paperwork, and hounding people by phone and email, added up to months of time.

Wafula left a culture free of schedules and entered highly structured schools. “After this, do this. After this, do this. I feel like I’m not living,” Wafula says of his first year in America. “Am I a machine? I’m not programmed by schedule.”

“It’s been a really tough uphill slog,” Roome says. “Studying is hard, often having to do things two or three times until you’re familiar with the system.” Yet, she says, “It’s been absolutely wonderful. We cannot imagine our family without him.” As far as everyone is concerned, he is their fourth child.

Meanwhile, tennis – the avenue that introduced Wafula to Roome and led him bravely into his new world – continued to change his life.

In the summer of 2016, after a one-week training session at No Quit Tennis Academy in Las Vegas, the academy offered him a scholarship to attend during his senior year because of his character and raw, natural ability. He moved from a quiet farm in rural Oregon, navigating, always with Roome’s steadying influence, not only America’s glitziest city, but also two school transfers and four to six hours of tennis training every day.

Through the academy he met well-known musician and singer Jewel Kilcher at her concert benefitting the academy. Impressed with Wafula’s charisma and story, she invited him to speak at her concert in Atlanta to raise funds for wells in developing countries – including Uganda. At a tennis tournament in San Diego, academy students shared their stories. Touched by Wafula’s story, Billie Jean King, a world-renowned tennis player, introduced herself to him afterward.

As he neared graduation, schools offered him scholarships for tennis – but tennis was only part of Wafula’s equation. He dreams of being a mechanical engineer, with a long-range goal of working for NASA. He wanted to pursue both tennis and engineering, and George Fox University was the right fit.

Forging ahead

“I give Jonah full credit,” says Roome. “He’s overcome some monumental hurdles. Culturally, I cannot begin to imagine what it was like. He’s had to learn it all from scratch.” But as hard as high school was, university is harder still.

“For the past three years, I feel like I’ve come a long way,” Wafula says. “I’ve learned a lot. But . . . every step I move, every level I go to . . . the more I feel like I have a lot to learn.”

Wafula likes to understand how things work. When his phone screen went on the blink, he looked for a way to open it himself to see if he could fix it. He’d like to do the same with his brain – open it up, switch things around – because studying and learning is different here. His brain needs to engage differently than the way he was conditioned growing up, both culturally and through severe early trauma.

“I have this thing for hard work,” Wafula says. “I don’t like to get things easily – the simple way. That thing has been in me, and even my professor knew. He says, ‘Jonah, you study so hard, but your results are little. You need to learn how to study better.’”

Staff at the university’s counseling and learning centers meet with Wafula to help him rethink how he learns. Professors talk through calculus problems. Friends and teammates study with him. But needing help adds another layer of difficulty. His mother’s advice echoes in him, and he wonders, If I don’t work hard, will I appreciate it? Is it begging to ask for help? “I feel like if I learn the easy way . . . asking for a lot of help . . . I’m not learning for myself,” he says.

Neal Ninteman is tennis coach, engineering professor and mentor to Wafula. “Largely because of his background, his experience, Jonah has determination and endurance that is extraordinary,” he says.

Along with taking difficult classes, Wafula volunteers in the rapid prototyping lab – a specialized area of engineering. “He’s taken the position because he wants to learn about everything in there,” Ninteman says. “He’s attacking this opportunity to learn.”

Wafula says he doesn’t get tired. “I just get frustrated,” he says, “but not tired.”

In his frustration, he speaks quietly to God in his native Swahili: “Listen, God, look where I am. If you leave me now, what’s going to happen? I am afraid I can’t do this without you. Will you bring back the promise – your protection, your guidance? Will you remind me what I am and the reason for being here, please?”

Chased by lions

“Because of what Jonah has gone through, he brings a perspective on life and sports that completes our tennis team,” Ninteman says. “He helps us look at what we’re doing in a different light – in a light that helps us perform at a different level.”

At one tournament last season, Wafula played the tiebreaker. “Jonah, are you nervous?” Ninteman asked.

“Man, I’ve been chased by lions,” Wafula answered.

Ninteman believes Wafula has the potential to become an All-American in tennis. “The raw material we’re talking about is out of this world,” Ninteman says. “And things like courage and guts and grit. He has amazing grit. Amazing. And the guys all come alongside him.”

While the physical focus and exertion of tennis, and the camaraderie of the team, help ground Wafula, his No. 1 goal is to pass his classes. “My mother has worked extremely hard raising us,” he says. “My job now is to study, finish my education, get a job I love and provide a better life for the people who have invested their time in my life.”

It’s a vision shared by Ninteman.

“What I’m most excited about is George Fox being the vehicle for helping Jonah find what he’s made for, to help him find what God has for him to do,” says Ninteman. “It’s cliché, but I really believe it. We’ll help him find his gifts and give him the skills to find his path.”

Wafula’s story is one of overcoming. It is one of poverty, trauma, nightmares, failure, perseverance and pride. The struggle to believe that humility – admitting to questions, asking for help – is a sign of strength, not weakness.

“I just believe God has a plan for me,” he says. “I just have to stick to God to help me, to motivate me to learn all this stuff in a different culture. There’s a reason why I came here. My own family is back in Africa, so I have a purpose.”

Bruin Notes

- Sand, Sobelson, Smith Inducted Into Alumni Hall of Fame

- Men’s Basketball Team Helps Build Court for Kids in Panama

- Chemistry Student Earns NASA Scholarship

- University Sets Undergraduate Enrollment Record

- Engineering Program Joins Elite Company with KEEN Membership

- George Fox Ranked ‘Best College for Your Money’ in Oregon

- In Print

- Seven Individuals, One Team Inducted into Sports Hall of Fame

- University Included Among ‘America’s Best Colleges’ for 30th Time

Alumni Connections

- Shelley’s New Book Challenges Readers to Turn ‘Bondage into Tools of Freedom’

- Gootee Joins Medical Relief Trip to Haiti

- Moreland Pursues Passion to Preserve Local African-American History

- Life Events

- News, by Graduating Year

- Harris Named President of Kuyper College

- Woo Honored by Oregon Independent Film Festival

- Wilmot Uses Graphic Design Skills to Help ‘Stomp Out Cancer’

- Send Us Your News