Stories of Faith, Grit and Joy

My Faith Story

Four seniors share about their faith journey at George Fox. Watch video

My Fourth Life

After flatlining three times, Ben Wing is living life to the fullest. Read more

‘Hope Dealers’

A group of George Fox use their vocational skills to serve in Philadelphia. Read more

- Wall Street Journal

La Familia lo es Todo

Dahlia is driven to represent her family and culture at George Fox. Read more

Art and Identity

Art major Alisa Hrushka shares her journey as an artist. Watch video

Leading With Hope

Portland Police Chief Bob Day draws from his own experience of loss to inspire hope. Read more

Baptisms on the Quad

George Fox students commit to follow Christ in the presence of friends and professors. Watch video

Resilience Personified

School counselor Mirna Pani models for her students what it takes to overcome hardship. Read more

From Firefighter to Counselor

Will Coker uses his counseling degree to care for the mental health of first responders. Read more

Not only has my faith grown, but my confidence in the calling that the Lord has put onto my life has as well.

Serve Day

Each fall, we shut down campus for an entire day to serve those in need. Watch video

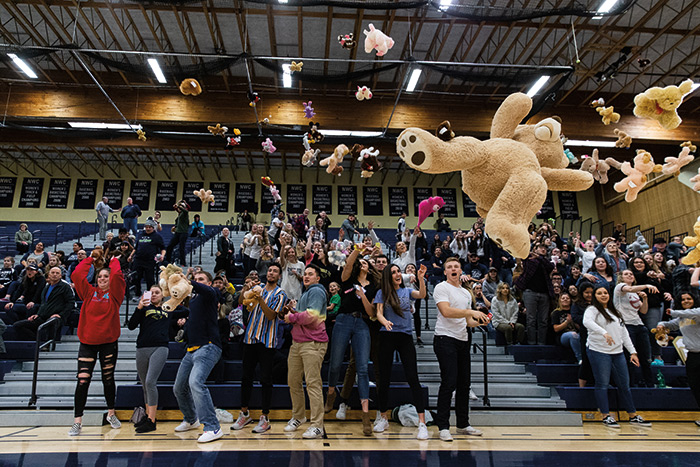

Night to Shine

George Fox students help create a prom night experience for people with special needs. Watch video

The Bouncinator 3000

A custom-made device gives a young girl with physical disabilities newfound freedom. Watch video

Full Circle

Peter Tran’s journey to becoming a nurse began as a cancer patient. Read more

What does it mean to Be Known?

Four students share how they’ve felt known at George Fox. Watch video

The Weight Came Off My Shoulders

When the burden of life became too heavy, Andrew Quach discovered God would carry him. Read more

Our student-to-faculty ratio

#beknown

Be Known Illustrated: Maddie Cognasso

Maddie was feeling anxious about her first big presentation, until an unexpected visit. Read more

Looking back at my time at George Fox, the only thing I would wish for is more time.

A George Fox Legacy – In Reverse

After four decades of waiting, it was Susan Marcu’s turn to walk across the stage. Read more

My Life@Fox

Follow elementary education major Shelby Franks through a typical day. Watch video

Human-Centered Design

Students in the Servant Engineering program design solutions for a better life. Read more

No Regrets

Senior Edauntae Harris shares his memories from an epic four years at George Fox. Watch video

Friday Flowers

Alumni hand out hundreds of flowers on the quad in memory of Grandpa Roy. Watch video

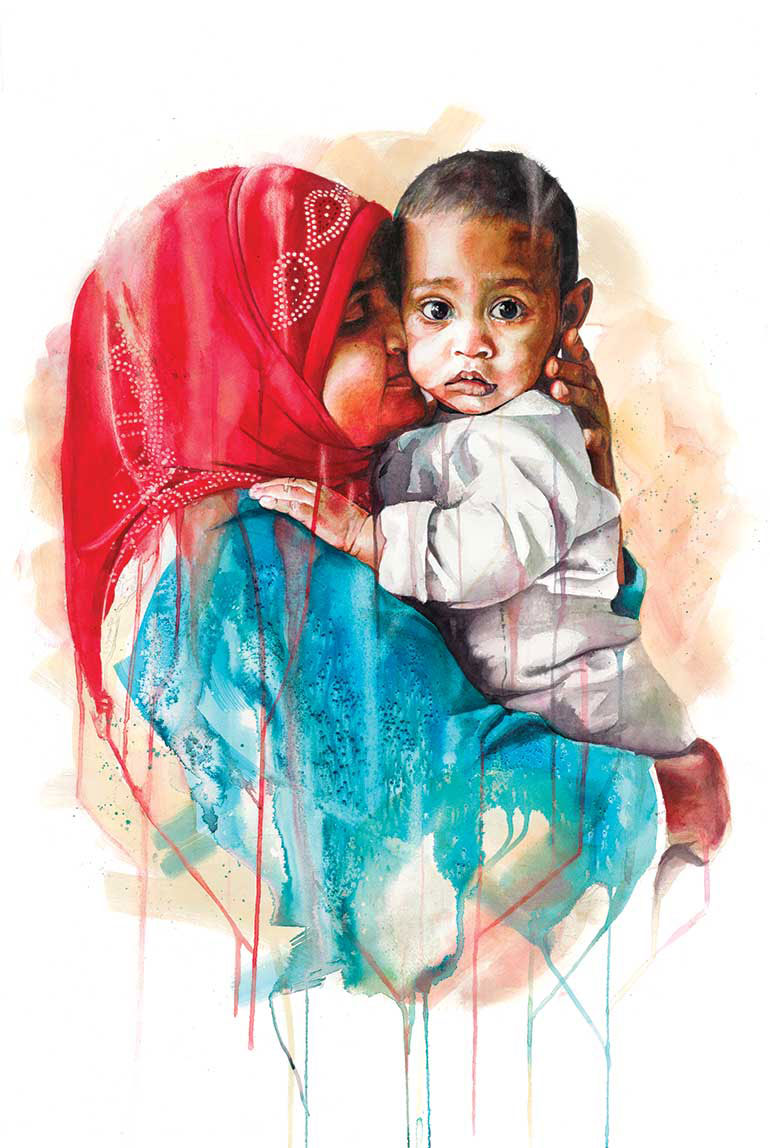

Art with an Impact

Karisa’s art amplifies the voices of local refugees. Read more

Fox brought me some of the best friends I've ever had and helped me find what I am truly passionate about.

Tierney Takes the Stage

Tierney Zubchevich walks across the stage to receive not one, but two diplomas! Watch video

Finding Her Voice

Nursing major Elysia Gonzalez is able to give others a voice – because she found hers. Read more

‘Nothing was going to stop me’

Annika Pears overcame serious health setbacks to complete her degree. Read more

Percentage of George Fox undergraduate students who travel overseas.

Jessie’s Juniors Abroad Adventure

Join Jessalyn Lim on an unforgettable study abroad trip to Spain and Portugal. Watch video

‘Here is Water’

An engineering class becomes a baptism when a professor and students answer God’s call. Read more

‘God is always going to be there’

A health scare and a tragic death in the family forced Anthony Pasion to lean on God. Read more

Strong at Heart

A life-threatening heart defect as a child fuels Emery Miller’s desire to help others. Read more

Proud Bruin Parents

We asked parents to share their hopes for incoming students. Watch video

This community has encouraged the growth of my faith above everything else.

La Roca

Javier Gutierrez Baltazar provides a solid foundation as a school counselor. Read more

‘Hope Is Healing’

After surviving the 2017 Las Vegas shooting, Marchelle Carl found a career in counseling. Read more

Be Known Illustrated: Estefan Cervantes Rivera

Connecting over a shared language created a special bond between Estefan and his professor. Read more

George Fox wasn't just about academics for me; it was truly transformative.

Number of NCAA team and individual national championships.

Refined Through Fire

The support of others during devastating events inspired Shaun Davis’ counseling career. Read more

‘Capable of a lot more than I imagined’

At George Fox, Dayana Caamal Perez discovered how God truly saw her. Read more

Friendship House

Adults with disabilities and George Fox students are live together, serve together and grow together. Read more

My time at George Fox has been life-changing in the best possible way.

Be Known Illustrated: Faith Burns

A group of new friends made Faith feel right at home her first day on campus. Read more

A Lifelong Dream Achieved

Ronnda Zezula thought school wasn’t for her, until she found George Fox. Watch video

Hours of worship, Bible study, prayer and service opportunities available to students throughout the year.

Be Known Illustrated: Sierra Scholtes

After a tragic fire, Sierra was surrounded with love and encouragement. Read more

Diving Deep

Health setbacks, then a pandemic, derailed Joanna and Jamie swim dreams – but rough waters only deepened the special bond with their coach. Read more

Exploring God’s Creation

Biology students take a trip to Boiler Bay to learn about invertebrate life. Watch video

The Heart of a Hero

When COVID-19 struck her care facility, Tracy Berg refused to leave her residents alone. Read more

I have truly felt known at George Fox.

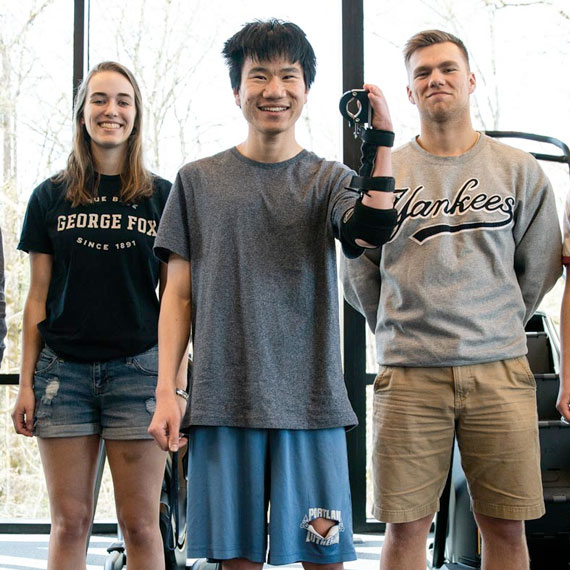

Strength in Numbers

Thanks to a servant engineering team, Evan Bonazzola finally got his day at the gym. Read more

Celebrating the Legacy of MLK

George Fox students participate in the Martin Luther King Jr. Day of Service. Watch video

Number of George Fox alumni

(and counting!)

Business Beyond the Bottom Line

His time as an MBA student informs Joe Ahn’s work more than a decade later. Read more

Never Give Up

Nancy Garcia faced several challenges in her college journey, but she didn’t give up. Watch video

‘Blindness Does Not Define Us’

Tracy Boyd found community, support and purpose in a group she created. Read more

My professors are incredible. They want to see you succeed in a way that’s hard to describe –the way a family roots for each other’s success.

Future Career: Superhero

Joseph Espero plans to use his DPT degree to make a difference in the lives of kids. Read more

Growing in Community

Kade Sorenson found the Christ-centered friendships he had always been looking for. Read more

Serving with Passion

Each summer, a group of physical therapy students and staff treat hundreds in Uganda. Read more

The Anti-Instagram

In an industry driven by likes, shares and followers, Greg Lutze stands out. Read more