Taking Aim at the Opioid Epidemic

Empowered by a $1.2 million federal grant, George Fox doctor of psychology students provide grace-driven care to vulnerable communities in Oregon

By Andrew Shaughnessy

On the day that Cara Bell* walked through the doors of the Providence Medical Group building in Newberg, she was at the end of her rope. Plagued by a history of trauma, abuse and methamphetamines, Bell was homeless, in and out of jail, and addicted to heroin. For a long while, she simply accepted this as her reality – just the cards that life had dealt her.

But when Bell discovered that she was pregnant, it turned her world upside down.

“She came in immediately,” says Dr. Jeri Turgesen, a primary care psychologist at Providence Newberg and a graduate of the George Fox Doctor of Clinical Psychology (PsyD) program. “She had so much guilt and shame around the fact that she was using heroin. That was a line she told herself that she would never cross. And the fact that she was now pregnant and harming another life was something that she really struggled with.”

*The name and some identifying information about this patient have been changed.

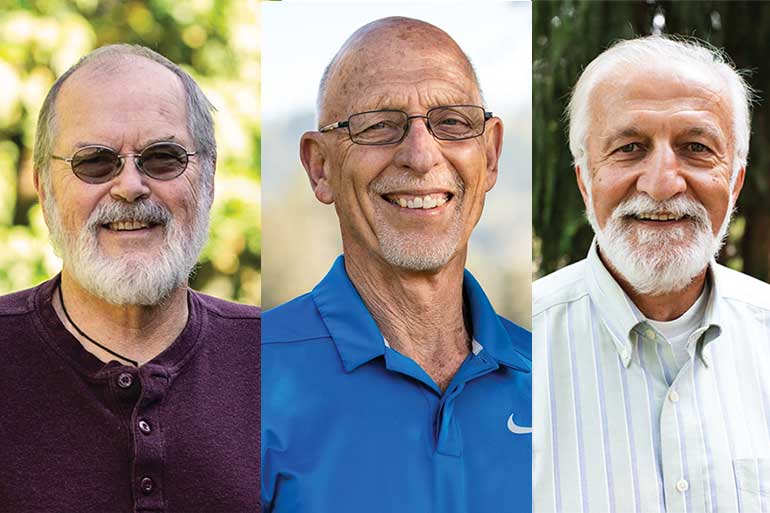

Jeri Turgesen, a primary care psychologist at Providence Newberg, is a graduate of the George Fox Doctor of Clinical Psychology program.

Right away, Turgesen worked with the director of family medicine at Providence Newberg to get Bell started on Suboxone, a drug used to treat opioid addiction. But that was only the beginning of a long journey of recovery. Turgesen worked with Bell for three years, providing a constant, stable source of support and human connection. For years, drugs had served as Bell’s primary coping mechanism – her way of dealing with anger, fear and pain. Without the heroin, she had to learn to navigate her emotions in a healthier way.

“We did a lot of work,” Turgesen says

Today, Bell’s life has completely changed.

“Her baby is 2 years old, and he’s adorable,” Turgesen adds. “She’s been sober for all of his life, plus eight months of his pregnancy. She’s working full time … and is no longer homeless.”

Turgesen still sees Bell about once a month, helping her work through her history of trauma and set long-term goals. “Watching her with her baby boy is incredible,” Turgesen says. “She’s an amazing mom and so devoted to her kiddo.”

Since graduating from George Fox in 2012, Turgesen has dedicated herself to providing holistic psychological help in a primary care setting. Working side-by-side with her colleagues at Providence Medical Group, she cares for countless people just like Bell.

“Most of our patients don’t know how to call a psychologist,” Turgesen explains. “Many times, I’m their first face of mental health. I love having the opportunity to be in a space where people go when they’re in crisis – to be able to respond in that moment is such a meaningful opportunity. It can sometimes be dirty and messy and hard, but the wins are incredible.”

Turgesen got her start at Providence a decade ago as a practicum student in George Fox’s PsyD program. Today, she trains students in that very same program – equipping the next generation to care for the hurting and vulnerable.

It’s meaningful work, and makes a real, tangible impact on people’s lives. Yet, in high-need communities like Newberg, there is a shortage of primary care psychologists equipped for the task at hand: trauma-informed, culturally competent care for people with opioid or substance abuse disorders. Just as troubling, local residents often lack the resources to access the help they need.

Now, armed with federal funding, George Fox and Providence Medical Group are tackling the opioid crisis head on, training the next generation of clinical psychology professionals and bringing free treatment to underserved populations. And Turgesen is right in the thick of it.

A Very Particular Set of Skills

It’s no secret that Oregon is struggling with a statewide opioid crisis. Some Oregonians, prescribed opioid pain medications after a surgery, get hooked on pills. Others turn to illegal drugs like fentanyl or heroin. Though policy changes have brought some progress of late (opioid prescriptions have steadily declined over the past few years), massive challenges remain and the human toll is all too real. Fentanyl overdose deaths are up, and according to the Oregon Health Authority, an average of five Oregonians die from opioid overdose every week.

In October of 2019, George Fox received a $1.2 million federal grant aimed at combatting Oregon’s opioid crisis. The grant provides stipends for eight students in the university’s PsyD program over the next three years, allowing them to provide free care for people with opioid and substance abuse disorders. Four provide care at the Providence Medical Group facility in Newberg – where Turgesen supervises and trains the students – and four more serve at the Chemawa Indian School primary care clinic in Salem, Oregon.

“This is an emerging field,” says Mary Peterson, director of the university’s PsyD program. “We already had substance abuse training in our doctoral program, but not specific training for opioid use disorder. Working alongside other providers in a medically assisted treatment model requires specific skills.”

“Our goal is to serve the underserved. We take God’s love and grace to the most vulnerable of our community.”

Through the grant, George Fox students receive specialized training and experience in trauma-informed care for opioid and substance abuse as well as in telebehavioral health – key for expanding access to mental health care services in underserved populations.

“The vast majority of our patients come in in the middle of addiction and active use, and then our plan is to help them safely withdraw from substances and then start on medication and treatment,” Turgesen explains. “Our goal is to get them as comfortable and stable as possible, with a medication-assisted treatment regimen. Then we can work on the emotional components of chemical dependency and psychosocial stresses. It’s really making sure we come up with an individualized plan for each patient that’s going to help them be most successful.”

Bridging the Gaps

Though the potential for life-changing impact is great, the challenges to providing quality care to people with opioid abuse disorder are daunting. According to the Oregon Department of Human Services, Newberg is considered a “poverty hotspot,” with 25 percent of residents living in poverty and struggling to make rent or consistently pay for food and utilities. These economic factors end up impacting people’s health care in significant ways.

“Let’s say a patient only has $5 left in their bank account,” says Turgesen. “They have to make the choice to buy food or fill up their tank with gas to come in for their appointment. These are huge barriers that our patients are navigating.”

Through telebehavioral health, Turgesen and the students she trains harness the power of technology to conduct remote appointments with patients in their homes, saving both time and money, and expanding access to those who would otherwise be unable to seek care.

Navigating the mental health system, finding childcare, and overcoming the stigma associated with opioid and substance abuse disorders also present significant challenges. By offering cost-free services in a primary care setting, George Fox doctoral students help bridge these gaps all in one fell swoop. “Let’s say a patient comes in to see their OB-GYN; they can see our graduate students right there at no charge,” Peterson says. “They don’t have to pay. They don’t have to navigate the mental health system. They don’t have to worry about going to some psychologist’s office and feeling uncomfortable as they’re sitting in that waiting room, so it reduces stigma. Oftentimes they don’t have to arrange childcare, because they can come in for a half-an-hour appointment during the day and can bring their children with them. That’s huge!” One of the eight graduate students benefitting from the grant is Joanna Harberts. Before going back to school to earn her doctorate in clinical psychology from George Fox, Harberts spent a decade as a licensed marriage and family therapist.

“One of the things that was important to me when I started at Fox was that I wanted a new and different experience,” Harberts says. “I got plugged into women’s health care, and I found that there were all these women who had no idea there were services available to them. They would be so overwhelmed, but they were able to come see their doctor. Many times the doctor would pull me aside and say, ‘Hey, I want you to come meet this client right now.’”

In November, congresswoman Suzanne Bonamici visited Providence Newberg to learn more about the unique partnership between Providence and George Fox.

“That warm handoff is probably one of my favorite things,” Harberts adds. “When someone is in a moment of crisis, and you’re able to go in and be that safe space for them right then and there.”

Four weeks into her time at Providence Newberg, Harberts is getting her fill of experience. She shadows Turgesen, taking patient histories, helping them sort through their stressors and triggers, and works with them to manage mental health issues. Over the next three years, she will work at Providence Newberg two full days per week and see a minimum of 12 patients per week.

“Before my training here, I didn’t have much experience working with addiction,” Harberts says. “This has all been brand new for me, but I’ve found that my training has prepared me to handle anything that comes into my office.”

Cultivating Empathy

Of all the skills these budding clinical psychology professionals learn, the most important may be empathy – seeing and treating patients as human beings made in the image of God, each with a unique story.

“Nobody asks for substance abuse disorder,” Peterson says. “Nobody starts a prescription thinking, ‘I want to get hooked.’”

When our entire experience of opioid abuse comes from the news – stats and stories about rising rates of addiction, wrecked lives, and drug-fueled crimes – it can be all too easy to lose sight of the human beings behind the numbers. Peterson hopes that George Fox’s program will cultivate empathy among students, helping them see the person behind the addiction and learn to look for and value their story and perspective.

“The vast majority – I would say 100 percent – of my patients have a significant history of trauma,” Turgesen says. “Either adverse childhood experiences, recent trauma, or some combination of the two.”

When it comes to helping patients overcome addiction, tapering off a chemical dependency with a drug like Suboxone is merely the beginning. The bulk of the work done by Turgesen, her Providence colleagues, and the George Fox graduate students is more focused on helping patients learn to identify and manage their emotions in a healthy way through practical tools and strategies. Just as important is the time spent on making meaning out of trauma, addiction and chemical dependency – reframing addiction as part of a patient’s experience rather than as the thing that defines them.

“So much of the language that we use when we talk about chemical dependency is very stigmatizing and pejorative,” Turgesen says. “Society asks: ‘Are you clean or are you using? Are you dirty?’ That can be so impactful and dehumanizing for patients – as if to be an addict is to be a bad person. But they have a life and a story and a history, a whole narrative on how they got to this space.”

“Sometimes with my patients I’ll try to think back to who they were before they used for the first time,” Harberts adds. “Often they’re born into situations where they didn’t have a choice. They did the very best they could with what they had.”

Working with people suffering from chemical dependency is not an easy calling. Yes, there are stories like Bell’s, stories of beating the odds and turning a life around. But there are also stories of struggle and pain and failure, of mothers and fathers, sons and daughters, relapsing over and over and over again, letting down the people they love, tearing themselves apart at the seams. Their stories are messy, and they don’t all have happy endings.

And yet, even amidst the brokenness and the heartbreak, there is the potential for incredible transformation.

“Our goal is to serve the underserved,” Peterson says. “We take God’s love and grace to the most vulnerable of our community. We take our stellar academic and clinical training and use it to make a difference in people’s lives.”

Peterson calls it a “sacred space,” this meeting between practitioner and patient, this beautiful entering into the messiest parts of a person’s life. As America continues to reel under the weight of a nationwide opioid crisis, our communities need more people like Turgesen and Harberts – highly trained individuals, equipped with a unique combination of head and heart, dedicated to caring for the vulnerable and hurting, people with the grace to look for hope in the cracks of broken lives.

George Fox and Providence are building those people.

Bruin Notes

- More than $139,000 Raised for Students Affected by Coronavirus

- COVID-19 Pandemic Leads to Spring Semester Unlike Any Other

- Faculty Members Honored as Top Teachers, Researchers for 2019-20

- George Fox Digital to Deliver Be Known Promise in Online Format

- In Print

- Development of Patient-Centered Care Model Puts DPT Program in National Spotlight

- Physician Assistant Program Set to Launch in 2021

- Rankings Roundup: George Fox Earns Top Spot Among Christian Colleges in Oregon

- Recent Recognition

- Scott Selected as New Provost